Here’s an excerpt from a memory book I’m writing. Some sections are built on related, even if partial, recollections—in this case experiences during my college years. At times, memories can be like bits of mica shining in a chunk of stone you pick up. The word mica comes from the Latin for crumb and relates to another Latin word meaning “to glitter,” according to web sources. As a kid with my friends, we’d often see rocks with tiny mirror-like flakes of mica embedded.

The Seventies has been called the Me Decade, but I dispute that casual label. Every decade is complex with high and low periods. Nixon resigned the presidency in disgrace, but the nation celebrated its Bicentennial. It was my coming-of-age decade, and life in America was churning. In some cases my personal story wove into the public story, such as being spared from the military draft as the U.S. was beginning to withdraw from the Southeast Asian war zone. I write about that elsewhere in the manuscript. A lot of people were moving in a communitarian and not exclusively individual way, including in Lowell where activists with local support combined to reframe the city as a national historical treasure.

The Freedom Train photograph below appears in my book MILL POWER: The Origin and Impact of Lowell National Historical Park (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014) and should also be credited to Marina Sampas Schell with a hat tip to Tony Sampas for getting it to me.– PM

Semesters Incomplete

by Paul Marion

One (3/74).

The Cherry & Webb Company of New England operated a women’s clothing store on the corner of Merrimack and John streets in Lowell for decades. The store had an alligator. I ran the alligator two nights a week and on Saturdays when I was a college sophomore.

Henry David Thoreau gives this advice: “If the laborer gets no more than the wages which his employer pays him, he is cheated, he cheats himself.” Every person at some time or another examines his or her work to determine whether or not such work is meaningful. By what yardstick does one measure such qualities? Should we ask ourselves if the job makes us happy? Is the end product or service useful to society? Does it make people’s lives better? Does the work degrade either producer or consumer?

It’s not unreasonable to aspire to doing work that is simple, useful, personally rewarding, and in harmony with the universe. Operating a manual-system elevator meets the conditions above. The work does not require deception in order to be successful. There’s no laying mega-waste to natural resources. Self-degradation is not necessary. It’s a service job—transportation. You meet people. Between rides, there’s time to meditate and do isometric exercises. With an empty car, sometimes I turned to face the back and ran the elevator blind.

All kinds of people walk into the elevator. Whether an aged woman with drab cloth coat and large shopping bags held by the handles or kids asking mummy to take them for a ride in “the alligator,” they all want to go either up or down. Among the characters who frequented the store was a burly dame who once wrestled one of our clerks to the floor and another time pushed a middle-aged drugstore manager through a plate glass window and onto the sidewalk. She crossed my threshold one afternoon, asking to be delivered to the “loose cloth” department. We had no such thing, but I quickly slid the door shut and deposited her on the third floor (Coats, Dresses, Foundations)—and descended.

Customers demanded to be taken to the TVs and record players. Sorry. A popular request was “Take me to the Basement, please.” They knew discounted clothes were on the lower level. But I can’t hear “Basement” without thinking of the nuns in Catholic grade school handing out a “basement pass” to a student desperately seeking a toilet.

As in most occupational cultures, the elevator business has its own jokes. The three standards, ranked, are 1) This business sure has its ups and downs; 2) You can go to great heights with this job; and 3) This job must drive you up a wall. Once in a while a too-serious person showed up and asked, “How many times a day do you go up and down?” I never counted. Most people were friendly and respectful.

The only real danger in this work is machine failure. The vertical up-down running in an interior shaft has many moving parts. Luckily, the elevator never quit on me, although it could be temperamental. In the corner of the passenger car I kept a T-shaped tool that was meant to be used if the car got stuck. The end of the tool fit in a round inlet on the floor. The problem was that I would have had to pull up two layers of rugged carpet covering the emergency disk. Passengers had the real answer to being stuck, of course. “Just bang like hell on the side of the elevator until rescuers show up.”

There were times that the elevator rode too high on the fourth floor and the motor stopped. In this situation I climbed a steel ladder on the outside of the building and walked across the gravel-over-tarpaper roof to a wooden shack that housed the engine. There, I took two lengths of 2 x 4 wooden stud and forced an electrical contact that set sparks flying and re-engaged the engine.

The roof is about twenty-five yards square. An assistant manager once said to me that it is the perfect spot to meet King Kong but let me say this is no skyscraper at four floors. I can picture the scene, with a little effort. The puny alligator man confronts the giant monkey on the sticky tarpaper roof above the ashen city below.

It was also on the roof that a cranky French-Canadian maintenance supervisor observed that all the TV antennae in sight were “arse-in-two,” that is, oriented to Manchester, New Hampshire, instead of Boston where the big stations were broadcasting signals. I couldn’t tell the difference. I think he was wrong. Why would he be the only one who was right? You can imagine what it was like to work with him. One summer when I was promoted to shipping clerk, he ordered me to sweep the stairs leading to the second floor. I said, “I don’t work for you.”

Two (9/74).

We asked if the political system had worked when it was through. The drumming of Washington Post reporters in 1972 had White House bag-men scrambling in the stew. Instead of counting dead Viet Cong, they dreamt pay-off sagas, talking “stonewall” and “tossing out the big enchilada.” Credible John Dean blew a factual whistle for Senator Sam Ervin. Richard Milhous squirmed, but knew Spiro Agnew had slipped “the pen.” The Saturday Night Massacre of Archibald Cox and company drew mail by the tons. Oval Office lawyers and crooked priests trotted out candid lines. Tricky-Dick televised his edited transcripts and said he wasn’t lying. But Judge Sirica persisted, the full Supreme Court said, “Give,” and New Jersey Congressman Peter Rodino, red-eared from screening tapes, found the high crime. Impeachment’s Goliath Sword sent Nixon scuttering west in a dethroned whirlybird.

Three (5/75).

The intramural Stragglers and Red Daggers played extra innings on the diamond looking north up the Merrimack River as far as New Hampshire hills where Robert Frost never left the woods. Afterwards in a downtown tavern, the softball players drank not enough beer and fought over Crazy Eights and bowls of pistachios under the creaky ceiling fans spun by leather belts and pulleys. Outside, marches by John Philip Sousa, a Portuguese-American giant, blared into the open bar door from loudspeakers on the Freedom Train, at rest on the rails by the canal gatehouse at Lucy Larcom Park, on route across country for the nation’s 200th birthday.

Four (6/75).

Federal authorities may want to canonize the locks and canals of the Mill Age and declare them to be St. Urban National Park of Lowell, Mass. Fishing trenches good for carp as big as tuna, splashing cannonballs of factory kids, and tires as smooth as honey-dipped donuts, earned a heavy-duty government physical exam in the coming budget year.

Five (8/75).

Speaking at a town meeting in Dracut, our Congressman, Paul Tsongas, said, “Don’t spend forty billion for the B-1 Bomber made to unleash thermonuclear terror after the intercontinental ballistic missiles and submarine warheads have destroyed the world umpteen times over.” We talked about such things at his regional town meeting, as well as renewable energy breakthroughs and why political leadership sucks so badly nationwide.

Six (10/75)

Professor Chris Smith asked, “What makes one thing Art and another thing not Art?” My class read Plotinus, Kant, Plato, and Aristotle to find an answer. In another University of Lowell course, Aldo Leopold from the 1940s urged us to value where we live as much as he loved his Sand County in the Midwest, if you can love that way. For a while, the Cultural Revolution and Modern Chinese Politics came out of my ears: Mao’s swim in 1966, capitalist roaders, the purge of Liu Shao-ch’i, “Bombard the Headquarters.”

At the Harvard Model United Nations, my campus club represented Iraq. In Widener Library, I spotted law professor Archie Cox getting a book. He had the same Special Prosecutor crew cut as he did on TV when Nixon ordered his firing. I spent a night drinking with the pretend-P.L.O. delegation and challenging Oklahoma Jim of the Sri Lanka team about his critique of the social morality of utopias. Make-believe Greek delegates from Bryant College of Utah danced in the hotel lounge to a pop group called Ox until they achieved a sweaty mess.

Seven (11/75).

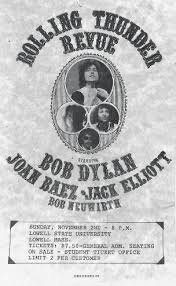

In Costello Gym on campus, wearing a feathered wide-brimmed gray hat, Bob Dylan could’ve been a Mexican balladeer on a new Durango song, bouncing on stage and stamping his whole leg in time to the drum. Ramblin’ Jack Elliot dedicated “Me and Bobby McGee” to Jack Kerouac, who as a kid had played King of the Hill on the sandbank right across the way on Riverside Street. Roger McGuinn brought out his “Chestnut Mare” with its fifty-nine lines plus chorus. To finish, the entire troupe, not the least of which was Joan Baez, plus Allen Ginsberg on jangling tambourine, sang Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” with everyone (including my girlfriend Marie after she had given tissues to a nosebleed guy she had dated one time in high school)—all of us choir-ing and clapping until basketball game lights re-flooded the space.

After an overnight in the Holiday Inn near the Pancake House at the junction of Rte. 495, Dylan and crew with movie cameras went all pilgrim on the Jack Trail led by one of the surviving brothers-in-law, Tony the Elder, who took them to the Franco-American School, a former patent-medicine king’s mansion and later a school that was once visited by a campaigning Jacqueline Kennedy, and adjacent small-scale Lady of Lourdes Grotto topped by a monumental Jesus-on-the-Cross under which Dylan stopped to be photographed in color for Rolling Stone magazine (the river sounding behind him), pictured not for the cover but a long splashy story (“The Pilgrims Have Landed on Kerouac’s Grave”)—there’s that pilgrim word again in New England context.

Early-November maples blazed gold and crimson. Bob and Allen G. sat cross-legged on the sun-warmed earth before the simple flat stone in Edson Cemetery, talking about the writer in the ground right there and the words “He Honored Life” cut into the tablet by the erudite school teacher and stone-carver Victor Luz of the monument company across the street. Allen read a bit from Mexico City Blues, whose choruses had rung in young Bob’s brain back in Minnesota and Greenwich Village, all those years ago. He was here to make a statement, to see for himself the place in the books, the land of origin.

Eight (11/75).

The Marlborough woods. Brown in their winter skins, they stand, lean pointers, borders of the wilderness. Glass branches dip and sway, and in the chilly distance across the top of Mount Monadnock, under a white flannel sun, wind blows the snow like cold smoke in the air.

Nine (12/75).

The good way Dan turned his head and dropped three nickels into the bent tambourine of the Salvation Army-man between sips of twenty-five-cent draft and bites of pretzel at the Old Worthen in one of the high-backed booths with his three friends who had stopped the cribbage game when the deaf Frenchman in a blue-green overcoat came to the table with eyes of a saint and handsome brown gloves that held the jingling pan so our good Christmas will would get us to push a few coins his ever-loving way.

“The Old Worthen” by Richard Marion, litho print, ink drawing with watercolor, c. 1975, Reprinted by permission of the artist.