by Paul Marion

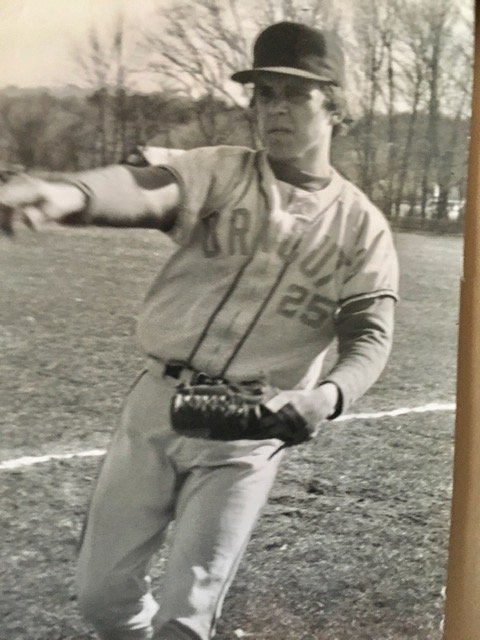

Dracut High School, 1972

IN THE 1950s AND ‘60s, small bottling companies “popped” up around the state. I grew up with Dracut Home Beverages, produced in the Collinsville section of town. The plant was little more than a retrofitted garage on a side street in a residential area off Lakeview Ave. I still have one of the branded bottles, now valued as a collectible in the region. We always called soft drinks “a tonic” because of the local source of tonics like Moxie that came out of the once-lucrative patent medicine business.

For several years in the mid-1960s, my cousins Tommy and Danny Brady in Lowell, about the same age as me, a year younger and a year older, had a small business selling cold drinks to players and spectators at softball games of the Lowell Industrial League at Hovey Field across the street from their house. Half the park was in Dracut with a baseball diamond at each end. My cousins packed ice between the bottles of vivid tonic and pulled the wooden soda crates in a little red wagon to the park. Each Saturday their father drove them to the bottling plant to buy eight cases of twenty-four.

Companies of that time included Raytheon Missile Systems, Joan Fabrics, Pandel-Bradford, Prince Spaghetti, and Avco Space Systems (a NASA contractor developing designs for Mars exploration). When we were twelve, the players appeared to be immense in size and as old as our fathers even though most of them would have been in their twenties or early thirties. I had a similar impression as a freshman baseball player in high school with eighteen-year-old seniors the size of forty-year-old men stomping around the locker room—a few of them bearded but not tattooed. Their home run clouts matched Harmon Killebrew’s. We knew the better players by names and numbers.

Between innings, softball guys paid a quarter for a seven-ounce bottle—maybe lime, strawberry, or ginger ale in crayon colors, among the many flavors. My cousins had the edge on the ice cream man in his ring-a-ding truck who swung by only once during the game.

“Hey, you kids, I sell the Cokes in this park!”

“Too bad, Mr. Softee. We’ve got it from here.”

We were getting to be business-minded in more ways than tonic sales. In 1968, my cousins and I discovered that we could buy a carton of Topps baseball cards for the wholesale price at the Notini Tobacco Company distribution warehouse in the old Little Canada section of Lowell. What a revelation. Cut out the middle man. In those days the price at the corner variety store was five cents a pack. Each time Topps released a new series for sale, we’d get a carton with twenty-four packs of five cards each at a discount. What wealth we had when we spread our fresh cards on the kitchen table. The thin, hard, flat rectangles of pink bubble gum got tossed in the garbage.

Around this time, Tommy and I were happy to be included in regular weekend pick-up games organized by my brother David and his friends, some high school buddies, some new college pals, who played six or seven on a side (the hitting team provided the catcher) if there were enough guys or alternatively played scrub with two men up at a time and others in the field. The regular field was the worn-down but usable Hovey Field reserved for softball on week nights. There was one day when Hovey was unavailable, so everyone saddled up in their cars and drove a half-mile up the street to a park on Pleasant Street in Dracut where there were two diamonds with outfields back-to-back. Past the outfield looking east rises the distinctive wooden bell tower of the Old Yellow Meeting House built in the late 1700s. We found a large squad of neighborhood kids, closer in age to Tommy and me than to the older guys in our gang.

After a quick negotiation, the locals accepted the challenge, and we had a full-on game set up with nine players on each side, maybe ten on the “home team,” each side providing an umpire calling strikes and balls from behind the pitcher during its turn at bat. What spooled out was epic, a full nine-inning game with fantastic fielding and clutch hitting, shortstops diving left and right to stab hard grounders, outfielders making impossible catches on long drives over their heads.

We could have played eighteen innings, like Ernie Banks of the Chicago Cubs: “Let’s play two!” We were semi-unconscious in our giddy good fortune. Time stopped for this field-of-dreams game. One kid ran across the street to his house to get jugs of water after the fourth inning. The absolute spontaneity, serendipity, harmonic convergence of factors lights me up even now. An “away” team shows up at your neighborhood field and challenges your crew to a game. This scene is from a book, a movie, a made-up memory like walking to school in a blizzard in the old days. We rhapsodize about the magic and mojo of hardball. The game on this day was pure for three hours. Two bunches of birds landed in the same open space and flashed their feathers. Everything anybody had in raw ability or learned-skill from thousands of bat-swings, rounds of playing catch, and patchy pick-up contests found expression in the heightened moment. We played for the joy of it. In high school I became friends with several of the kids we played against in the game of the decade. Bobby and Mouse Dionne, Bones Beaudry, Donnie Beaudry, Gene Topjian, Dennis Doucette who lived across the street, and Gary Sullivan, who later joined the priesthood.

Monahan Park, then Pleasant Street Park before it was dedicated to Michael Monahan who had been killed in Vietnam, was already part of town baseball lore, remembered in a poem by Bob Schaefer, who had been at second base during a Little League game in the early 1960s when emerging sports-god Kenny E. (later a college football star and after that my high school civics teacher and baseball coach) belted a titanic home run that soared past the outfield, over the chain-link fence along the sidewalk, and across Pleasant Street into the front yard of the Fox family home. Nobody had a tape measure, but spectators knew they had seen something for the first time. In Dracut this was like Babe Ruth and Ted Williams.

I have no idea who won the ballgame in Dracut Center. The contest is etched in my mind like no other in many years of what some would call unorganized baseball but for me was a long-running series of entrepreneurial ballgames, as democratic a thing as you will find. Everyone got chosen for a team. We followed official baseball regulations and applied local ground rules, depending on location, whether farmer’s field or taken-over Little League diamond. For example, second base might be a flat stone too large to dig up. Disputes were negotiated by team captains if there was no agreed-upon umpire at the start. Having an umpire was once in a hundred games—maybe somebody’s dad showed up and offered to call safe-and-out on the bases. The next day your team would be a new mix of friends competing against yesterday’s teammates. We learned a lot about getting along.

We used our own just practices like “bucking up” for first time at bat. We decided “first ups” in one of two ways. In the bat toss, one kid tosses a bat to another who catches it with one hand half-way up the barrel. Then the kid who tossed the bat closes his fist above the catcher’s hand—and so forth until there is no room for another hand. The top hand wins. Unless, of course, a crafty kid calls “tops” and wins by slapping his palm on the knob of the bat. For “odds and evens,” two kids, each with a closed fist, say “Once, twice, three,” shaking their closed fists three times. On the fourth shake, “Shoot,” each puts out one or more fingers. Before any counting or showing fingers, one or the other of the kids, by mutual agreement, would have called either “Odds” or “Evens,” meaning the total number fingers shown determines who wins.

Everyone played. Take “Rollies at the Bat.” Except for the batter and a catcher, all the players take the field. There’s no pitcher. The batter hits the ball out of his or her own hand: toss it up and take a cut. The hitter then lays down the bat lengthwise at his or her feet. Whoever catches or stops the ball then throws the ball in from the field, trying to hit the bat on a bounce or a roll. Rare is the throw that plunks the bat on the fly. If your ball knocks the bat, you become the next hitter. And a hitter stays up until a ball meets the bat.

One day when I was sixteen, the assembled neighborhood stars in the farm field at the top of Janice Avenue made me king for the day or something like that. We had about six players. One kid pitched to me for an hour. I swung the bat until my arms ached. One after another, I drove line drives and deep flies to four kids in the outfield who were having a fielding bonanza, chasing down balls in the gap, backing up on high pops, and grabbing liners over their shoulders. I was hitting so many balls that I started placing drives so that all fielders were getting their chances. This is something that does not happen. One person hitting for such a long time. It never happened to me again. Anyone who has played baseball knows the existential jolt a hitter feels from wrist to gut when the sweet spot of the bat connects with a thrown hardball. Boom, boom, boom. When he was playing hardcore fast-pitch softball in his twenties, my friend Mark used to say that hitting a home run was better than sex for him. He was into it. I forgive his exaggeration. Like the nine-on-nine pick-up game that materialized out of park air in Dracut Center in the summer of 1968, my day in the trampled-down farm field with woods bordering three quarters of the outfield remains a peak day in my years of unorganized ball.

My organized baseball time lasted four years. The old neighborhood at Hildreth Street and Janice Ave. with its full supply of kids gave me all the happy baseball that I wanted until I turned fourteen years old and wondered what it would be like to play in the town Babe Ruth League. With a fifteen-year-old age limit, the spring of 1969 would be my last chance to compete against the best players my age.

I signed up for the player draft in January and waited. My brother David had played a season or two of Little League and tells the story of wanting badly to play on a real team. We have a photograph of him in his itchy woolen uniform standing in our front yard with his fist jammed into the pocket of his fielder’s glove and looking serious, dark cap tilted a little on his head. He felt guilty because my father had to buy him a new glove to play. I’m sure whatever glove he had been using around the yard was a ragged leather thing: rawhide lace through the fingers tied together where it had broken from wear and the palm with a hole in it taped over with black electrical tape. He got a new glove. I watched him in a game at Intervale Field in the Kenwood section of town to the east and not far from the Merrimack River. He cracked a bat hitting a double down the left field line, a ground-rule double that bounced into the woods. After the game, the coach gave him the bat to take home. It was like a war souvenir, a saint’s holy relic, an actual new Louisville Slugger that had been carried to the field in the coach’s army duffle bag, a trophy whose handle David wrapped as tightly as possible to allow for further play at home. We made a bat rack out of a board and ten-penny nails for our three family bats including the cracked one. The bat handles were wedged between two nails that were not pounded in all the way. The knob overlapped the nails to keep the bat from sliding out. It was as fine as a gun rack in Kentucky.

Waiting for the Babe Ruth League team announcement, I tried out for the high-school freshman baseball team. We had enough good players to field freshman, junior varsity, and varsity squads. The coach posted the roster with typed names on the gymnasium door. Without having played an inning of town baseball, I somehow made the team as an infielder. A couple of weeks later, the Babe Ruth teams were set. Several freshmen played on Babe Ruth teams. If a schedule conflict arose, the high-school team had priority.

Returning Babe Ruth players stayed on their teams from the previous year. New player names, either first-year kids stepping up from Little League or entirely new names like mine, were put in a pool for league coaches to draw from. Coach Paul Lord selected me for the Yankees, which was a new team added to the expanding league. Dracut had so many kids about my age that the school committee instituted double-session attendance for my ninth grade. Not only was my 330-member class split between the high school and junior high buildings, but we also were on staggered schedules. For half the year, half of us started school an hour early and ended after lunch while the other half began at 9 a.m. and stayed until 3:30 p.m. The bus schedule was crazy as were after-school activities. I wound up in the junior high building. The teenage overflow spilled into town baseball. Hello, Yankees.

Paul Lord was Donald Trump before Trump was a thing. Coach Lord had golden-hay hair swept across the top of his head not to cover baldness like Trump’s but to manage the full mane atop his wide skull. He was a car salesman, of course, and drove a late-model Cadillac. He looked like Trump. He swaggered like Trump. He was an enthusiast who clapped his hands a lot on the sidelines. He often dressed in golf gear from white cap to stylish slacks and sporty shoes. I never saw him in sneakers. I heard that he chose me sight-unseen because of a rumor that I was a “ringer” who had played in California the year before. (In those years, my dad worked eight months a year in the wool business in central California. The family tried living there, but my mother couldn’t stand being away from her life back East.) Coach Lord didn’t know I had been in town my whole life, almost, except for the six months out west. But I got picked and proved myself when the new team met to practice. I wanted to pitch. Coach Lord let me try throwing from a regulation mound. He loved it when I dropped down and threw sidearm fastballs without tipping my delivery until the last second. Years of practice in my back yard paid off. Bobby across the street had a catcher’s mitt and had always been ready to take throws. I poured it in to Yankee catcher Greg Dillon, with whom I later played in high school. I mixed in a few curves, but I threw heat mostly, high-low, inside-outside. In my father’s time, these were called riser, sinker, in-shoot, out-shoot. We had a top-notch shortstop candidate, so I gladly took the third-base spot for the games when I didn’t pitch.

We did not disappoint Coach Lord even though the Cardinals finished first. They were loaded, including the best freshman player (he had made the JV team), Brian from the House of Burgesses in Kenwood, eight brothers and a sister, a full team at home. You did not want to take them on in the neighborhood. They would crush you. Albie Demaris from my own neighborhood fired fastballs for the Cards. All’s fair. At mid-season the league sponsored an All-Star Game. Because the Yankees had the second-best record, Coach Lord was in charge of our side. He gave me a new ball to start the game. With my dark blue baseball cap pulled down low to shield my eyes from the sun, my mother said I looked like Denny McClain of the Detroit Tigers who had won thirty-one games the previous year. Halfway through the season, my pitching and hitting had gone remarkably well.

On a night when we started with a game that had been suspended due to darkness a couple of days before, I singled in the winning run with a man on third base in our last “ups.” After a fifteen-minute break, the umpire said “Play ball” to begin the second game. We played all seven innings of this one, and I threw a one-hitter. The next day, I got my only newspaper headline of the season: “Marion Dracut B.R. Star.”

On the other hand, I had a patchy high-school career. Overall, I was simply thrilled to make the freshman team and to stay on the roster the next three years. I didn’t play in many games the first year, but I showed the coaches that I could hit fast pitching. If I had opted for an outfield position instead of shortstop or third, or even said I could pitch, I probably would have played in more games over four years.

Sophomore year, a few of my classmates moved up to the varsity team. The coaches kept me in play as starting shortstop for JV. I hit well enough in the first half of the season to be promoted to the varsity squad a few times to give them an extra bat. One game stood out. Billerica, another of the Greater Lowell suburbs, had a pitching juggernaut even several years before Tom Glavine starred for the Billerica Indians on his way to the Atlanta Braves and Baseball Hall of Fame. In this Billerica home game, Dracut was being no-hit by Fred Wiroll and Ed Minishak, the team’s best arms and maybe the Merrimack Valley Conference’s dominant hurlers, our region’s Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale.

“Get a helmet and a bat, Paul, you’re going to pinch hit,” said my coach Tom Tobin, motioning to home plate.”

Coach Tobin, medium height with dark hair, slightly resembling President John F. Kennedy, taught history at the junior high in town. He encouraged the players and never yelled at anyone. He knew his baseball and taught me to crouch lower when fielding ground balls at shortstop, where I made my share of errors. He didn’t want me to go the route of Don Buddin, a Red Sox infielder of the late ‘50s whose nickname was “E-6.” I liked the coach’s kind demeanor. In the fall when I started at Merrimack College in North Andover, he called me at home to say he’d given my name to the Lowell Sun sports editor who was looking for correspondents for high school football games. I took the assignment, my first writing job and byline, my first time in print.

Neither team had scored until the bottom of the sixth inning. The situation had Billerica ahead 2-0 with two outs in the top of the seventh, our last chance at bat. I stepped to the plate, took a ball low and inside and swung through the next pitch, a waist-high fastball. Minishak in his green-and-white uniform must have been thinking that I was a sacrificial lamb, some JV bench-warmer thrown up there in a desperation move. I knew I had to hit the next pitch or else I’d be hacking to stay alive. Everybody on the bench stood up.

“Just get a piece! Good eye, now! Swing hard! You hit that ball, Paul Marion!” When they said your two names, you knew it was serious.

I dug in my back foot. The speedball tailed to the outside. I half-stepped with my left leg and took a short stroke, quick and level. Crack! The skipping ground ball found a hole between the first baseman and second baseman. Clean single. I got on. Broke up the no-hitter.

An ounce of pride was saved for the Middies (The school’s sports name is a long story involving a hurricane and the Naval Academy.) The next batter made an out. Beating us in the final game of the season gave Billerica the Conference championship. Our record was three wins and thirteen losses.

My other high-school highlight, two in total, comes from a senior-year extra-innings game in which I played the outfield and got three hits, a double and two singles, against Andover High School, which always fielded a strong team. In the top of the tenth inning, Brian got an infield hit, stole second and third, and came home on an error with what proved to be the winning run, 5-4. We didn’t win often, our record being five wins and seven losses with three games to go.

The next game I was pumped up, expecting to be penciled into the starting line-up. Coach Tobin pulled me aside.

“Paul, I’m putting Taylor in right field today so I can swap him out for our starter, Ricky, without having to take Ricky out of the lineup if we need a pitching change. I want to keep a lefty in the batting order.”

This sounded reasonable even if bad news for me. I nodded and headed to the bench. So much for getting three hits in Andover. For my cooperation, I received a gold trophy at senior awards day which reads: “A Really Great Team Player.” I’ve got it here on my desk as I’m writing.

The lowlight of high-school baseball is that my father never got to see me play. He didn’t see Babe Ruth games either because at that time he worked spring and summer in the California wool industry. In the years when he was back in Dracut, he had a late-day work schedule. Once in my senior year he came to a home game at the field behind the high school gym. We talked a little before the game. I rode the bench one more time. My big contribution was coaching third base. Lots of chatter for the batters, relaying signals to men on base, and waving a few runners in to score.

My love of baseball has as much to do with my father’s passion for the game as anything else. On a Sunday in May 1964, the year before the Minnesota Twins had a 102-win season and gained the American League pennant, my father took me to Fenway Park to see them in a double-header against the Sox. I may have liked the Twins more than the Red Sox that summer. Tony Oliva, Harmon Killebrew, Zoilo Versalles, Jim Kaat, Bobby Allison. With the 1964 baseball cards, I began to follow the players.

Dad drove to Boston without complaint, in fact, I think he was glad to have somebody to go with. He parked the car, and we walked to the ballpark, always a stunning sight inside, the greenest lawn-green, white chalk lines, tan infield. I had been there once or twice before. Dad bought standing-room tickets because the grandstand was full, and he didn’t want to sit in the bleachers. We found a good spot on the concourse behind the last row of seats, not directly behind the catcher but looking slightly up the first base line. We stayed for the two games. He knew I wanted to see every minute. He stood for six hours of baseball. We got hot dogs and drinks, a tonic for me and beer for him, twice. In the eighth inning of the second game some fans had left, which opened up a couple of seats. The teams split the games, 2-6, 6-5. That’s what I was remembering when I looked over at him in the bleachers from my spot in the third-base coaching box.

In its way, baseball prepared me for the high degree of failure in the writing trade. Hitting safely one out of three times makes a top-notch major-league slugger. For batters, the game assumes regular failure. Collecting rejection slips from magazine editors and publishers can make a writer humble and thicken his or her skin—which is what makes writing success such a thing to savor.