Patti Smith’s New Book

BACK FROM THE DENTIST in the city where I used to live, I checked my mailbox and found Patti Smith’s new book that I had ordered from amazon.com, the big river of products seemingly in the sky overhead. Year of the Monkey from Knopf publishers is a far flight from her start in poetry with Seventh Heaven from Telegraph Books, a short, skinny book that I looked at fifty times but did not buy when I was a part-time clerk at the big yellow bookstore in Chelmsford, Mass., one town away from where I lived and had grown up. I was out of college a couple of years and had met the owner, Eric, as a customer, and we would chat at the counter, which led to a friendship, he from New Jersey like Patti, having bought the store after seeing a newspaper notice and being eager to try something new after doing ads for Macy’s.

Patti, a public-college student in New Jersey because that’s what her family could afford, was a classmate of a writer-friend of mine, Nancye, a longtime arts-and-entertainment reporter for the Lowell Sun, who now freelances from her house on the Maine coast, theatre her specialty. In college she and Patti said Hi to each other in the student publications office where Patti volunteered for the literary magazine and Nancye edited the yearbook. They didn’t engage, which Nancye regrets, now that we all see what happened. Patti tells interviewers she wasn’t outgoing at that age. She wanted to be a writer, she was writing, but Nancye didn’t save any of the early work if she had copies.

The monkey in Patti’s book makes me think of the Monkey Bridge in Heidelberg, which has had a sassy bronze animal on a wall near the bridge entrance since the 1400s. Custom has it that a person who rubs the monkey’s fingers is destined to return to the city on the Neckar River, which felt like Germany to me, having been in Germany only a few days and seen a couple of other cities, like Dusseldorf. Heidelberg has a warm tone, perhaps set by the romantic castle high above the historic business district, or maybe it’s the beer halls. One of the souvenir shops outside the castle had a large Ben & Jerry’s ice cream poster covering half the front door. The city is a short bus ride from the Rhine River for travelers like my wife, Rosemary, and me, who spent a day there last August, late in the month, when many of the locals were on holiday in Switzerland or France. A popular “old town” site is the antique student jail once used to lock up drunks who managed over the years to turn the holding cells into a geode of cartoons executed with surprising proficiency. Did the warden hand out brushes and paint pots to the blitzed scholars?

The monkey story reminds me of the picaresque scenes of Mark Twain in action or that he reports observing in his book A Tramp Abroad, something like autofiction if you wrote it today—This is what I did, this is what I’m thinking, but not really, not exactly, because I can’t show you a movie of my every moment, each of the supersonic messages in my brain. Germans have a word, kunstlerroman, for a book about a writer coming into his or her own as a person and an artist, but that’s not what Twain was doing. He spent the summer of 1878 with his family in Heidelberg, Zurich, and Florence, and fashioned his experiences as a long walk, the “tramp” being the excursion, not a reference to himself as a hobo. Tour guides in Heidelberg tell Americans that Twain may have chosen “Huckleberry” for a character name after learning that the city was built on what was called Huckleberry Hill for the area’s robust blueberry-like bushes. Records show that Twain was already writing the Huck Finn book and had the name. But it’s a good story for the tour guides.

Twain hiked with a make-believe friend, twinning fact and fiction, dreams and reality, not unlike Patti Smith’s method in the new travel book that takes her from San Francisco to Kentucky to other places, in her case usually solo, unusual for a celebrity but she seems to get away with it, all the while slightly destabilized by a friend’s dire medical condition and the declining health of playwright Sam Shepard, one time her boyfriend and now a cosmic always-friend. From the first friend’s bedside in S.F., she heads south to L.A. and San Diego, wandering, I could say sauntering in the old sense of the word, a saunterer being a searcher on the road to the Holy Land, sainte terre. Think about Patti’s road, St. Francis (a favorite city of her Beat favorites), St. James (Diego), City of Angels, St. Ann (Ana) the sainted cross (Santa Cruz), down along the loaded Mission Trail on the coast of the Golden State, not to overlook San Juan Capistrano where Rosemary and I toured the restored mission last winter, taking a photo of the Royal Road (El Camino Real), six hundred miles south to north from San Diego to Sonoma. Patti takes photos all the time when she’s on the move. Some of the images are reproduced in her book.

On her somewhat random journey, Patti meets brain-tunnel types who talk about Roberto Bolaño’s novel 2666 and mason jar-canning entrepreneurs. An ethereal Japanese cook materializes and makes soup for Patti’s scratchy throat. Like Twain, she’s in the moment as well as around and above the moment, making the moment that she composes later for the finished story. I don’t know how many of these scenes along the road are straight from her notes or jump shots of mind that come later—remembered fragments, some of the passages voiced like clipped Sunset Strip crime noir while other segments are outtakes from her brain-movie, Alice from Wonderland and peppy Pinocchio in key roles coming back from girlhood.

Patti’s is a dream book but not another Book of Dreams like Jack Kerouac’s (1960), published by City Lights in San Francisco (there’s that place circling back), his strange volume with eight years of transcribed fantasmic overnight features in Jack’s noggin, the cinematic shorts in his own private movie-house all “auteur”-like and highly plastic in their reality like the reports from Patti’s dreamscape that enter her book. When she came to Kerouac’s hometown, Lowell, Mass., in 1995 to celebrate and thank, I think, Jack-in-heaven, Patti read poems and prose and then sang with musician-friends, including an earthy “Dancing Barefoot” in bare feet on a cheap Persian rug covering the makeshift stage at Smith Baker Center, an abandoned Congregational Church across from City Hall, the same stage that Allen Ginsberg and colleagues, Corso, Ferlinghetti, Michael McClure accompanied by Doors keyboardist Ray Manzarek, had performed for the benefit of Mr. K. in late June 1988, surrounded by one thousand people, a full house, the night before the dedication of the Kerouac Commemorative sculptural tribute at French and Bridge streets downtown. Lowell Franco-American operatic bard Gerry Brunelle and I read that night also but we were like Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock the raggedy morning after, not much crowd left when we took our turn after the stars, squashed cups in the aisles, forgotten jackets on seats.

Smith Baker Center, named for Rev. Smith Baker, not for two guys like the Smith Brothers on a cough drop box, is caving in but could be preserved and made to look like a smaller version of Ryman Auditorium in Nashville, the Grand Ole Opry country-music temple. Kerouac writes about walking home after school past the church’s “profound bloodred bricks . . . the brown lawn, the jag of snow, the sign announcing speeches” in his love-and-loss youthful romance Maggie Cassidy, another town-and-city story by the master of dualism. McClure would later tell California Magazine that the group reading in Lowell was the most important poetry reading of the year in America, and that says something doesn’t it? Manzarek read Mr. K’s words sandblasted into polished red-brown granite at the Commemorative and declared the whole thing “subversive.” He and McClure agreed that such paragraphs and poems are never cut into stone for the ages, and that this treatment had up to then been allowed only for politicians and generals, maybe a minister here and there or even a god. Thousands of words in granite pillars for as long as they can resist the acid rain.

My friend Nancye had a family event the night of Patti’s gig at Smith Baker, so didn’t attend the show, but her pal at the Sun, Dave, music guru in his own right, was on assignment and carried Nancye’s college yearbook to the show for Patti to sign, which she did, remembering their student times. I think Patti knew that Nancye had been dancing more than once on the American Bandstand TV show in Philly with host Dick Clark. The loop closed for a time machine-second. Patti was coming off a long absence as a performer as well as the recent passing of her husband, Fred “Sonic” Smith, a musician also, and gave Dave a lot of time in a pre-show phone interview, reflecting on music and the world at large. Dave wrote later that the interview was his favorite in twenty years.

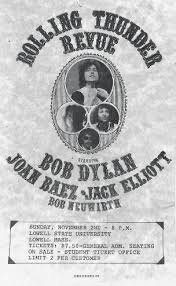

![“Lowell State University” [wrong name] concert flier; Joan Baez and Bob Dylan, 1975](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/571d2a1460b5e99d45a5d739/1600092842207-4N2P3QKRC3FDU1ZK98Z0/dylan+baez+1975+lowell.jpg)

![Marion’s Meat Market in Little Canada in Lowell, Mass., c. 1925 [Photo (c) Paul Marion]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/571d2a1460b5e99d45a5d739/1573780101666-64H7P2S070UKMARRW3CL/marionsmkt_tcm18-314808.jpg)

![Wilfrid and Antoinette Héroux Marion, at the Hi-Low “park” in Little Canada, Lowell, Mass., 1917 [Photo (c) Paul Marion]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/571d2a1460b5e99d45a5d739/1573782036080-DUINBAU3V2TLKW38XICP/Wilfrid+Antoinette+1917.JPG)

![Wilfrid Marion, far left, with his friends dressed in their Sunday best at the Hi-Low “park” near the Merrimack River in Little Canada, Lowell, Mass., 1916 [Photo (c) Paul Marion]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/571d2a1460b5e99d45a5d739/1573780896306-2D776EEXLDZLRX942O0M/IMG_3175.JPG)