The informal panel talk described on the poster above will include commentary about and music from “The White Album” as well as the speakers’ reflections about the momentous year, 1968. I was asked by the organizers to provide the local context for the record’s release 50 years ago—November 22 to be exact. I took the assignment for a ten-minute talking slot and made notes that turned into a script, which became a short essay. The end product is longer than I had planned, but as I researched and wrote I picked up more relevant information and my thinking expanded. I needed a structure for my presentation, so I kept going. For the event two days from now, I’ll pull highlights from the essay—facts, anecdotes, passages that will give the audience a sense of the late ‘60s in Lowell, Mass. Below is the full essay for anyone who would like to read the long version, very different from “Revolution 9” as long versions go.

1968 and ‘The White Album’ in Lowell

Prologue

JOAN DIDION’S NOW-CLASSIC 1972 book The White Album begins: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” In her essays, she’s not writing about The Beatles as much as tapping the vibe of the late 1960s to say what it felt like to be alive in that moment. Didion’s world was shifting and eluding meaning—improvisation had upset a solid storyline. She writes, “We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the ‘ideas’ with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.” She started questioning her assumptions. Events were overtaking the expected pattern. Even The Beatles were shifting from a tight band to four separate players and back again in their double album called The Beatles and more famously “The White Album.”

“Helter Skelter,” a hard-rock song on disc two, whose name comes from a type of playground slide in England, got turned into an obscene threat by the murderous Charles Manson cult in 1969. Manson, a criminal and self-proclaimed prophet, concocted a twisted interpretation of “The White Album” as an apocalyptic forecast. A group of Manson’s followers butchered five people in Los Angeles, including the actress Sharon Tate, who was pregnant. Things were still falling apart, the center still not holding—a situation consistent with Didion’s earlier take on modern American culture in her first book of essays, Slouching Toward Bethlehem.

My Time

I was born in Lowell and grew up in the town of Dracut close by. In 1968, I finished eighth grade and started high school. To that point I was obsessed with two things: baseball and The Beatles. My family never missed the nightly news on TV, and my parents read two newspapers each day, three on Sunday if my older brother bought the New York Times. We were a current events family, so I knew what was going on. But my political awakening at fourteen years old didn’t happen until I saw the police thrashing anti-war demonstrators on live TV during the Democratic Party’s national convention in Chicago.

A cousin of mine, Marc, traveled to Chicago with friends from UMass Amherst to protest and was beaten by cops. He’s six years older than me. Marc had the longest hair of any of my cousins and looked and felt like the Sixties to me. His girlfriend was an artist. We never spoke about his politics, but I watched him and soaked up any news about him from his mother, my aunt Rollie. (He intrigued me as a little kid because he had pictures of New York Yankees baseball stars in his room—not Red Sox. The Yankees were winners in those days.)

My rising opposition to the Vietnam War boiled over as I watched the chaos on the Chicago streets and heard young demonstrators chanting, “The whole world is watching! The whole world is watching!” Unforgettable scenes and words that shaped me.

A few years later, when reading Norman Mailer’s account of the conventions of 1968 in Miami and the Siege of Chicago, the vivid description of that clash in Chicago jumped off the page and stoked my emotions again. The Chicago convention radicalized me, if that’s not too dramatic for a fourteen-year-old. When Graham Nash sang his song “Chicago” at Boarding House Park in Lowell two summers ago, he lit up my nervous system again with these passionate lines: “We can change the world, rearrange the world/It’s dying—to get better.” Just about everybody knew the words and was singing loudly. “If you believe in justice . . ./And if you believe in freedom/. . . open up the door.”

“The White Album”

In late November 1968, my friend Susan in Dracut walked three miles in the rain to buy the new Beatles double album at a Lowell record shop and hitchhiked home when the paper bag started to soak through. “I was one crazy Beatles fan,” she says.

At college, another friend, John, a photographer now, remembers “the beautiful color prints of the boys” that his roommate had taped to the wall. Around the same time, the Rolling Stones released their Beggars’ Banquet recording in an off-white sleeve, a second “white” album. John says it took all weekend to “fully consider both albums . . . listening deeply, testing our understanding of the music and lyrics, poring over the liner notes for hidden communiques.” He adds that The Beatles’ plain white album cover was excellent for rolling joints because “the small bits of weed stood out nicely.” John says the music didn’t catch hold of him and his friends until after winter break and the first half of the year. There were thirty new songs to absorb—in so many styles, with so much content.

My lifelong friend Paul recalls friends from high school who could afford to buy the album “debating for months whether it was as good as Sgt. Pepper or a hodgepodge of John’s and Paul’s songs.” Some of them thought it was a mess. He says, “Beatles’ songs [the group and solo] in 1969, ‘The Ballad of John and Yoko’ and ‘Give Peace a Chance,’ were overtly political, but not as clever as the lyrics to ‘Back in the U.S.S.R.’ or as poetic as ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps.’”

Speaking globally, a growing-up classmate of mine, Willy, says: “To have been lucky enough to come of age as those first Beatles songs hit the airwaves was akin to grabbing the lightning bolt right out of the sky.”

My experience with “The White Album” lagged. When the album landed, I was still listening to Beatles’ songs from 1964 and 1967, A Hard Day’s Night and Magical Mystery Tour, plus a handful of number-one singles that I had on the small records, 45s. At later high school dance and beer-drinking parties, “The White Album” sank in thanks to a hundred spins on the turntable and repeated eight-track tape plays. “Back in the U.S.S.R.,” “Rocky Raccoon,” “While My Guitar,” “Bungalow Bill,” even the kooky “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” got us going in the town basements and city living rooms. Before and after the drinking age dropped to 18 years old, we had in our crowd two sets of parents who said they’d rather have their kids drinking downstairs in “a cellar full of noise” than drag-racing on the highway and tossing beer cans out the window if a cruiser fired up its blue lights. Anyone was welcomed to stay over. Nobody crashed a car.

We rocked out to The Beatles, Stones, Grand Funk Railroad, Crosby-Stills-Nash-and-Young, The Who, and lots of others. But The Beatles provided the musical anchor, “The White Album” and Abbey Road dominating. For about ten minutes I was in a makeshift band that tried hard to copy “Rocky Raccoon,” a mash-up of folk and honky-tonk showing the group’s incredible range. As an older guy I go back to “The White Album” for select cuts like “Long, Long, Long,” a gem featuring George’s voice and guitar with Ringo’s massive drumming.

My friends and I didn’t connect “The White Album” to politics at the time, even with the song “Revolution” on the disc and the not-so-subtle commentary of “Piggies” and “Happiness Is a Warm Gun.” We took The Beatles for music first and almost exclusively. That’s what we needed. The sound and the energy. We took them secondly for fashion, hair and clothes.

Lowell Time

Lowell’s population in 1968 was about 94,000—92 percent white, 5 percent Hispanic, 1 percent black, and .7 percent Asian. (The 2010 census showed 52.8 percent white, 17.3 percent Hispanic, 6.8 percent black, and 20.2 percent Asian.) Twenty thousand people left the city between 1920 and 1960, many of them World War II veterans like my father moving their families to the ring of suburbs.

After World War II, unemployment in the city rose and stayed high. The authorities began tearing down old houses, tenements, and business structures, hoping to attract new companies with open space for expansion. According to one report by neighborhood leaders: “The Lowell region was one of eight major urban centers in the U.S. classified as places with chronic unemployment, and as late as 1965 the jobless rate was 50 percent higher than the national average. From economic deprivation grew crime, neglect of the young and the elderly, poor physical and mental health, dependence of public welfare programs, and the steady withering of community involvement and spirit.”

A friend of mine walked to high school from his home across the river from downtown. He summed up what a lot of young people saw in the city. “I could have taken a bus, but walking the route, surrounded by empty mill buildings with broken windows, somehow reinforced the new independence I felt since leaving grammar school. Everything was bigger, and older, than the town I knew. History had been made here—had been—but the Lowell I walked through every day from 1968 to 1970 was spent and gray, punctuated only by the burnt-orange brick mill walls.”

Community leaders involved in the federal Model Cities urban renewal project talked about rehabilitating Lowell’s history, mills, and canals as a way to revive the spirit and economy of the city. At the grassroots, activists planned a way forward. They believed in education as a stimulant and pictured a “City of Learning” in a museum-without-walls. Ten years of effort led to tremendous change by 1978, when the city was named a national park, commemorating the Industrial Revolution of the mid-1800s, and the new computer industry created jobs in the region.

On the Streets

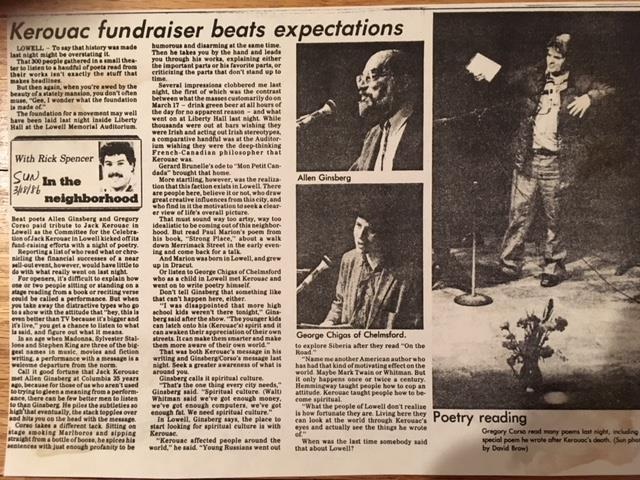

In the nation and world every month of 1968 brought an explosion, from the brutal Tet Offensive in South Vietnam that revealed the strength of the opposition to the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy, as well as student turmoil in France and Mexico and the Soviet Union’s invasion of Czechoslovakia.

By 1968, the Vietnam War was in Lowell’s bloodstream. In 1965, Army soldier Donald Arcand, 19 years old, was killed in South Vietnam near the end of his tour of duty—the first Lowell man to die in that war. He was riding in a helicopter that was shot down by fighters on the ground. He had played basketball at St Joseph’s High School. Jane Hoye, who was engaged to Donald when he was killed, wrote years later that she felt an “indescribable sadness” at the news of his death. She added, “There were no men in Lowell in those days. They were all drafted.”

![Students from the two colleges in Lowell marching for peace. (Courtesy of UMass Lowell, from To Enrich and to Serve: The Centennial History of the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, by Mary H. Blewett and Christine McKenna [Dunlap])](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/571d2a1460b5e99d45a5d739/1541554793465-CLJDEMPTRNQPG34534KR/antiwar+march+1970.jpeg)