March 2, 1977

Doing the Beat poetry bit: Anne/Snyder, Tom/Ferlinghetti, Steve/Rexroth, Ken/Kerouac, me/Corso. Steve says to me, "You are so audial, you sound like a blind man reading."

March 17, 1977

St. Patrick's Day. An unpredictable meeting. Three new poets showed up, one, Esther, published in The New Yorker and The Nation in the 1960s; another, Paula, a near-psychiatrist, read richly worded persona poems about a carnival and Dancing Bear; and the third writer, a wacky talky woman calling herself the Erma Bombeck of poetry, jabbered at the podium and read a few things. Many of us went to Lynn's after the meeting, where we drew lots for the April reading: I will go 18th. Tom had all kinds of clippings and papers to show me. He is enthusiastic. A wild session.

May 1, 1977

To Tom Mofford, I wrote, "Saturday was a fine day. I said to Annie Fleming, 'I feel like an outlaw when I go into Cambridge like this.' We stopped to watch an inning of a pick-up softball game on the Common. Lilacs on residential streets. Tall walls of steel, blue steel & glass. Italian steeple, brown triple-decker tenement, Anglican church, white Episcopalians, full decks of apartments street by street. Thick sandwiches and chips, iced tea, at the Blue Parrot eatery. Because I don't go in often, the trip remains an adventure. I like being this type of cultural bandit. We went into Cambridge and got us some live Robert Lowell. An afternoon full house at Harvard. Lowell reading golden oldies and recent work. His over-the-counter furtive stare and understated mid-poem remarks. With his pushed-back white mane, he seemed aged and far away at the podium. He's some kind of world-class 'local poet' in this setting, almost like a family room but extra large. In the audience, wasn't it good to spot celebrities like one of our own, esteemed Andover poet Stephen G. Perrin, and that other important author, John Updike, with his ruddy mug? I keep seeing the remarkable colors of the day: beds of crayoned tulips, fat stars of Chinese cherry flowers, slippery dark cherry bark, pink crabapple blossoms. There was a woman in a silver space-cadet jacket and a known Irish scholar with manila curls wearing a slim red tie. Each sunny stained glass window in Sanders Theatre made a kaleidoscope. Thanks for introducing me to the Grolier Bookshop. Some men show younger men the way to cathouses or cheap whiskey, but you chose a gem of a poetry store." [Robert Lowell died on September 12, 1977, in New York City. The May reading at Harvard was his last appearance there.]

May 1977

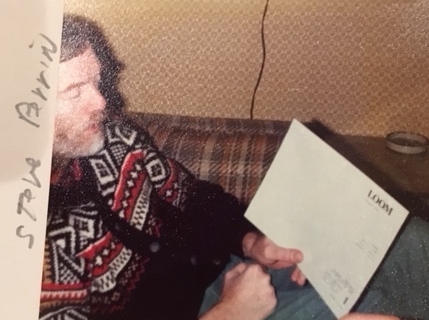

"All words with Z in them are suspect," Steve Perrin announced. When he was a kid he was taunted by this in the schoolyard: "Perrin is a Huguenot, Perrin is a Huguenot." Just kidding. Back to Z: Bozo, Oz, Cardozo, zed, zenith, syzygy, yazoo, Zorro, Lazarus, gazebo, garbanzo, Boz Scaggs, ozone, Zebu, Zulu. Tom Mofford at times approaches angelic, his face nearly beatific hovering over a pizza pie. At the same time, Tom is tactile like Doubting Thomas who needed to probe the wounds of Christ.

May 19, 1977

Great reading last night at the Parker Library in Dracut by the Poets’ Lab, nine of us. The audience numbered about 20. The poets read many very good new poems. We went out for pizza and beer @ the Walbrook restaurant after. I read “Smelling Like Childhood,” “Boys on Bicycles,” “Camille Flammarion,” and “Memorial Day Bridges.” For the intro to the reading I used e e cummings’ “Advice from a Poet” out of his biography by Charles Norman, which I had given to Steve to read in his class. Steve was written up in the Salem, Mass., newspaper—good recognition! He read a fine poem on “Responses.” Alice read a few moving grief poems based on nightmares and her husband’s death in London. Charlie read 4 pieces drawn from his anti-nuke stance and subsequent arrest and jailing in Seabrook, N.H. Cindy read a funny poem about eating out alone, reading a paperback. A marvelous reading all in all that went about 60 minutes. Tom made a flourishing finish. Too bad more people could not participate. When they hear it was so good, they’ll say, “Sorry we missed it.” That’s what the unicorns said to Noah as the Ark pulled out of the harbor.

October 5, 1977

Tom, Steve, Ken, Dave, Eric, Ruth, Cindy, Wayne, Eric, and three new people attended. Eric read his "Snadra Nad Our Pnats" poem. I don't know where he got the nutty idea of inverting the "n's" in this piece. But it's funny. Jersey Linder. Eric is from N.J. Cindy did a poem for me: "McDonald's & Marking Fresh Ice," referencing my second chapbook. Wayne read "Cromwell Road" with "history mines" and "brandied eyes." Gave Tom a letter on his poetry. 7:30 to 8 p.m. for business; 8 to 9 p.m. for poems.

November 3, 1977

Cindy said her computer dating poem will be published in a local magazine. Eric read "The Pearl You Spit Is Ancient Fishbone."

January 25, 1978

Alice Davis brought an anthology of Maine poets, Surf, Sand, Pine, which has her poem "Pink Trimline Telephone." A review of the book praises her writing as having "resonance." Alice also reported that she had poems accepted by North Shore Magazine and Dark Horse. Kathy Aponick had a poem accepted by Poet Lore magazine. Steve Perrin landed another poet-in-residence appointment at a school on the North Shore.

February 23, 1978

Alice shared her poem from a recent issue of Maine Times and then read a powerful sequence of 10-12 grief poems based on her experience after the sudden death of her husband in London in 1968. Wayne read a poem in the voice of a black soldier in the Civil War, saying it was written in response to Robert Lowell's "For the Union Dead." Florence had a poem evoking California's "golden magnet" and luscious oranges, while Mary read her version, comically fractured, of the legend of Passaconaway, regional Native American leader of the 1600s. Nine people showed up last night.

March 15, 1978

I called Charles Simic to ask about the Master of Fine Arts in Writing Program at the University of New Hampshire in Durham. He said to drive up to see him on March 28, Good Friday.

March 28, 1978

Charles Simic said, "For me, writing poetry is like breathing. I have to write or I would die. I happen to be teaching now, but I'd be writing poems even if I was a street cleaner, sweeping the streets." I needed to hear a poet I admire say that.